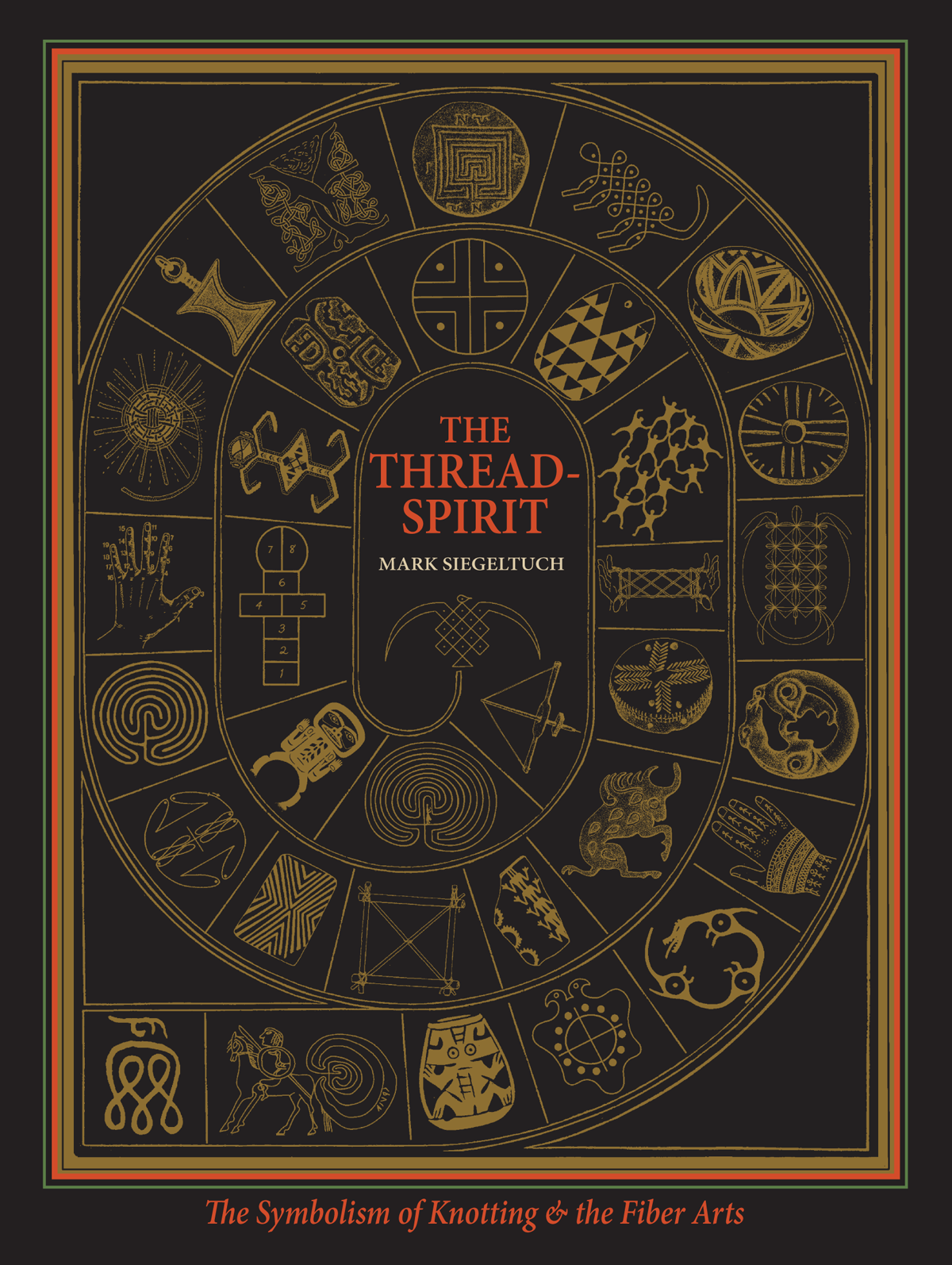

The technology of traditional societies is based on the application of metaphysical principles to practical ends. This is particularly clear in the case of the fiber arts— knotting, weaving, spinning, basketry, and the like—where a worldwide symbolism exists which appears to have its origins in Paleolithic times. Dr. A. K. Coomaraswamy referred to this symbolic complex as the sutratman (thread-spirit) doctrine and it is well documented by the literary, artistic and archeological remains.

Using a consistent set of symbols, our ancient ancestors sought to explain the relations governing the social order, the workings of the cosmos, and the mysteries surrounding birth and rebirth. The eye of the needle, for example, was understood as the entrance to heaven while the thread was the Spirit that sought to return to its Source. Creation is a kind of sewing in this version of the story as God wields his solar, pneumatic needle. Man is conceived as a jointed creature similar to a marionette or puppet but held together by an invisible thread-spirit. When this thread is cut, a man dies, comes “unstrung,” and his bones separate at the joints.

It was the American art historian, Carl Schuster who first discovered the significance of body joints in this symbolism and he believed that it was based on an analogy with the plant world where regeneration is possible from a shoot or sprout. Body joints play a role in such diverse matters as labyrinths, continuous-line drawings, cat’s cradles, dismemberment and cannibalism, and various rituals meant to ensure rebirth and the continuity of the social order.

Joints were also conceived as the knots of the body. It was originally believed that the spirit of a specific ancestor inhabited each body joint. The body as a whole served as a map of the social order, and by extension, the cosmic order. Joints were later used for counting, an extension of their original role in identifying social relations. Joints were replaced or supplemented by bones or knots and by Neolithic times we find a widespread distribution of knot technologies for counting and record keeping. The Inca quipu is the best-known example. These technologies preceded and supported the growth of numbers. Knotted cords were also used for measurement and for teaching music.

Cosmologically, it was believed that the earth turned around a pole (axis mundi) and this provided a model that was applied to all devices or natural phenomena that rotated (spindle whorls, drills, mills, wheels, whirlpools, whirlwinds, etc.). Because the seasons were brought on by this rotation, these devices became models of birth and death, time and Eternity.

Interlacing and knotting were meant to signify marriage bonds within the group and an especially elaborate symbolism was worked out to specify these relations. It was Carl Schuster’s belief that this symbolism was derived from the use of tailored fur garments, man’s first clothing.

There is much more to this story but what is clear is that there is an underlying historical continuity to this symbolism that survived from the earliest times until it was weakened by writing and finally forced underground with the rise of rationalism, at least in the West. These traditions survived longer in the East and into the 20th century in more remote parts of the world, but they were generally no longer understood.