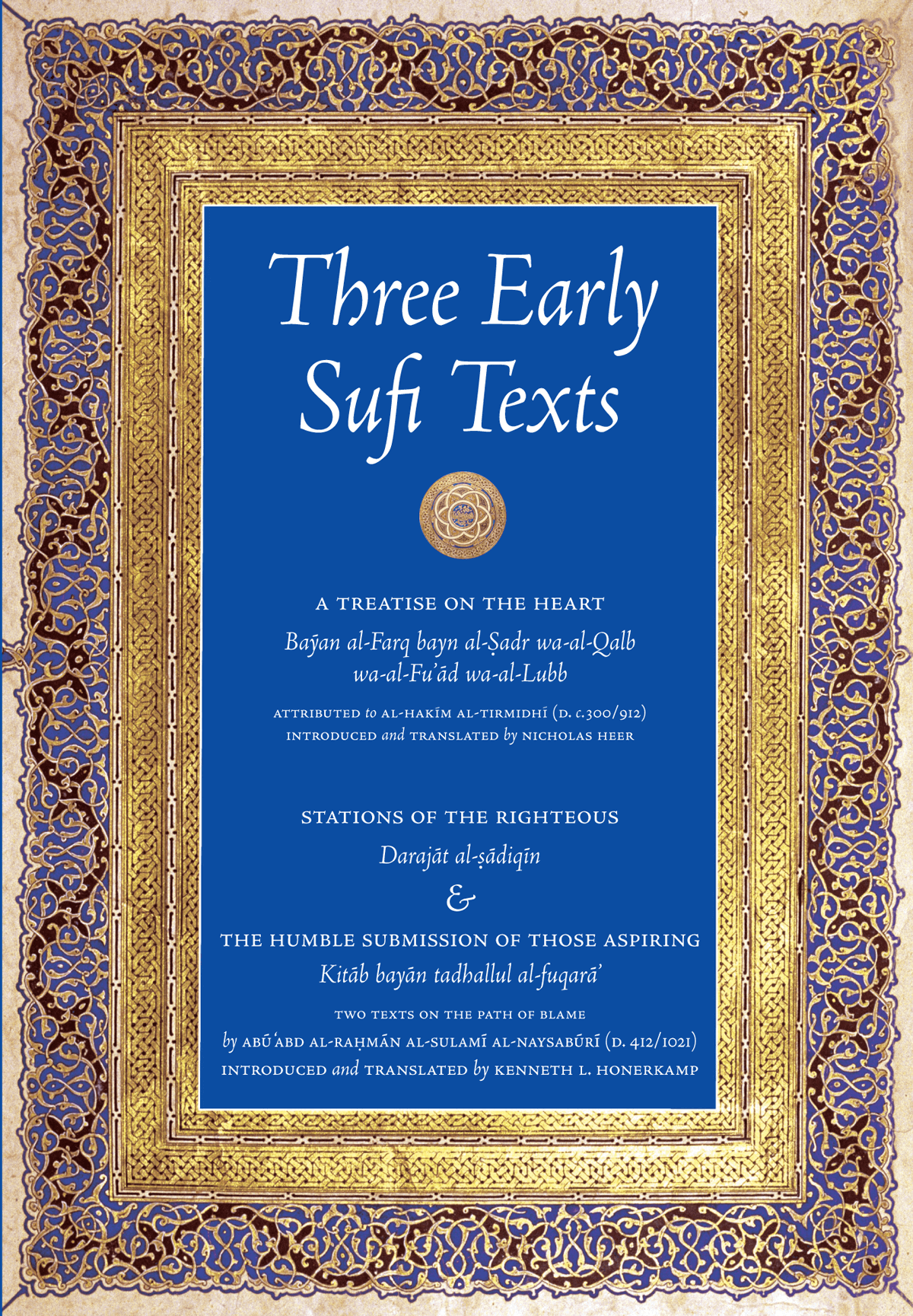

Three Early Sufi Texts: A Treatise on the Heart

$26.95

The three Sufi texts published in this volume all deal with some aspect of the Sufi path to God. The Sufi path is marked by a number of different stages or stations (maqam/maqamat) which the Sufi traveller (salik) passes through as he advances on the path.

A Treatise on the Heart

by Al-Hakim Al-Tirmidhi

The Stumblings of Those Aspiring

Stations of the Righteous

by Abu’Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami al-Naysaburi

Translations of texts from the formative period of Islam are rare. Those that were done are now out of print. Translations of Tirmidhi and Sulami are even more difficult to find. The three, previously untranslated works presented here originate from the pens of two of the most eminent figures of the Khorasanian tradition, Hakim Tirmidhi (d. 300/912) and Abu ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Sulami al-Naysaburi (d. 412/1021).

These texts, dating from the formative period of Sufism, affirm the existence of an already highly developed school of Muslim psychology that provided the foundation for the transformational process referred to within multiple spiritual traditions of the spiritual journey. Hakim Tirmidhi portrays the science of the soul within the Islamic context.

In Stations of the Righteous al-Sulami deals with the inherently defective nature of the soul, and delineates the path the soul must travel towards purification and the roles it assumes on its journey.

In Stumblings of Those Aspiring al-Sulami shares with his aspirant how best to manage the itinerary and avoid the pitfalls and obstacles of this journey. These three works are relevant within the domains of human spirituality and psychology for both the specialist and the non-specialist.

Within the history of Sufism classroom these texts offer some of the earliest and most concise examples of classical Sufi methodology to appear in translation. Those committed to the study of psychology, as the science of the human soul and its states, will find within the terminology and insights offered in these works relevance, which is historical, as it is conceptual. These works also offer anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the human spirit a mirror, at once timeless and personal, of our own human nature.

*Updated & Expanded Edition*

- 9781887752510