INTRODUCTION TO MA`DIN

Ma`din ul-Ma`ani [A Mine of Meaning] belongs to the malfuz genre of Sufi Literature. This genre was developed in India by the early Chishti Sufis. Indeed, it was Fawa’id ul-Fu’ad [Counsels for the Heart], an account of what transpired in the assemblies of the renowned Sufi, Nizamuddin Auliya (d. 1325), between the years 1307-22, that popularised this form of literature. It was a direct result of the reluctance of the early Chishti Sufis to put pen to paper themselves. The compiler of the work was Amir Hasan Sijzi, a noted Delhi poet. It was a common practice for Chishti Sufis to hold assemblies in which the master would speak on various topics or answer questions. It was a sort of free-flowing tutorial. The compiler would obviously be a regular participant in the assemblies. The fact that Sijzi was a poet indicates his competence to undertake the task. He would write up an account of what transpired shortly after the assembly while it was still fresh in his memory.

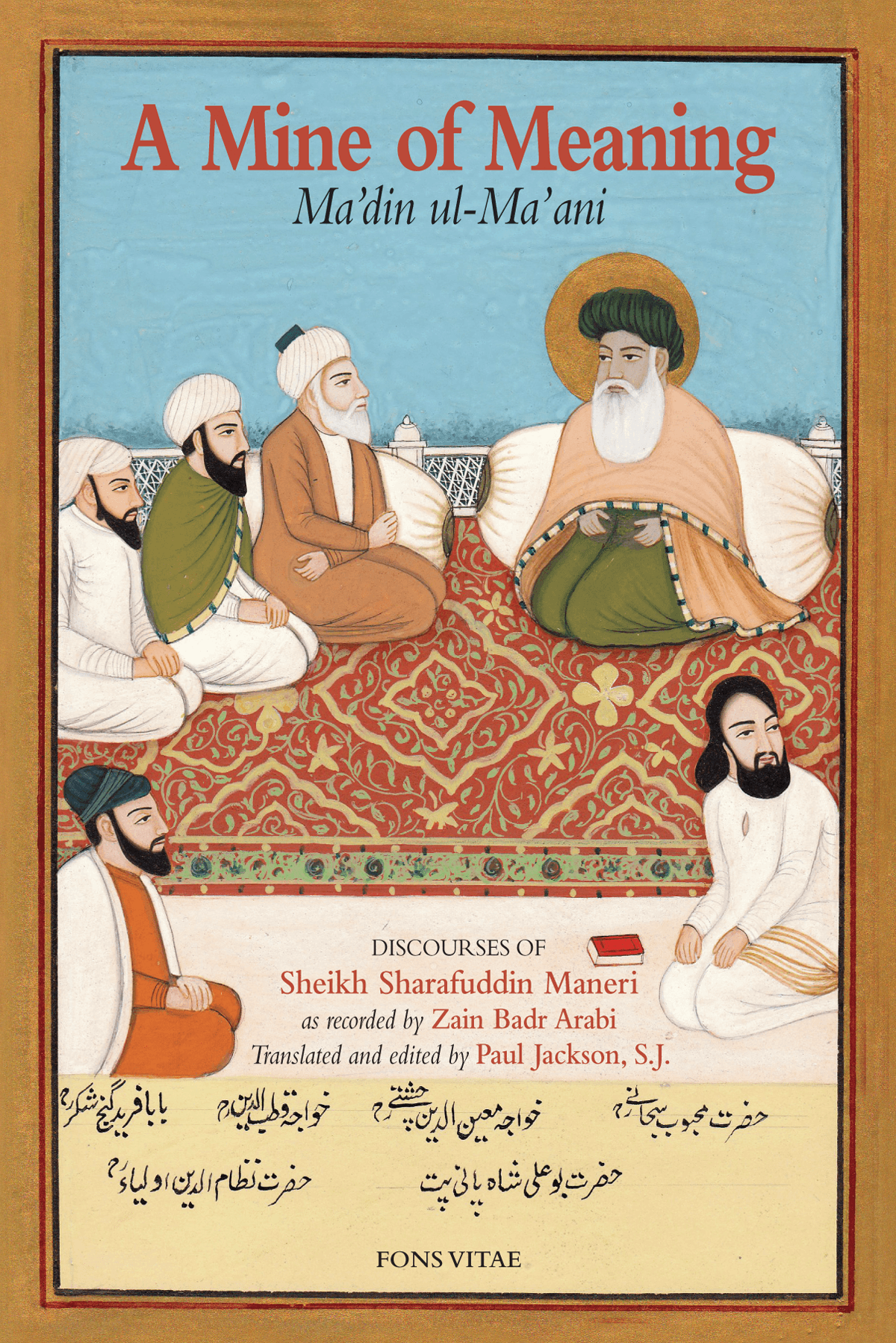

A Mine of Meaning is the fourth translation by Fr. Paul Jackson, S.J. concerning Sheikh Sharafuddin Maneri. It was preceded by translations of his two collections of letters, Sharafuddin Maneri: The Hundred Letters, and In Quest of God: Maneri’s Second Collection of 150 Letters. It is also the second of two accounts of what transpired during his regular assemblies, the first being Khwan-i Pur-Ni’ mat: A Table Laden with Good Things. He has also published The Way of a Sufi: Sharafuddin Maneri, an account of his life and teaching based on the persian source material.

These records were normally chronological in nature. Often the actual date of the assembly was given, and even the time of the day. This is not the format followed in A Mine of Meaning. To begin with, no dates are given in the work itself, which was compiled by Maneri’s faithful secretary, Zain Badr Arabi. If we turn to Khwan-i Pur Ni`mat [A Table Laden with Good Things], however, we discover when the work was completed. A Table Laden with Good Things was, in fact, the second malfuz compiled by Zain Badr Arabi. He wrote: “After the completion of the first volume of the discourses of the Master, known as Ma`din ul-Ma`ani, there was completed, from the 15th Sha`ban 749 [8th November 1348] till the end of Shawwal 751 [30th December 1350], whatever came into the defective hearing and deficient understanding of this Helpless One.” Throughout his writing Zain Badr Arabi refers to himself as “this Helpless One.”

This information clearly states that the work was completed prior to 8th November 1348. It also indicates the time frame in which Zain produced his second volume. It covered a period of two years. Moreover, it contained forty-seven assemblies, but these varied greatly in length. Nevertheless, the work does act as an indicator of the way Zain worked.

Zain provides another important piece of information regarding the chronology of A Mine of Meaning. He was also the compiler of the letters written by Sharafuddin Maneri to Qazi Shamsuddin, the official in charge of the township of Chausa. He wrote: “At various times, from the region of Bihar, in the year 747 A.H. [24th April 1346 to 12th April 1347], he ordered them to be sent to the aforesaid township [Chausa] to the petitioner just mentioned [Qazi Shamsuddin]. This is the collection the servants and attendants who were present in that dwelling place compiled from those letters, arranging them in the following order so that, on the day and hour when grace befriends them, they might put into practice what they have read.”

Although Zain refers to “servants and attendants” who were involved in compiling the letters, “arranging them in the following order,” it is clear that the bulk of the work was done by Zain himself. Maktubat-i Sadi [The Hundred Letters] was a huge literary enterprise. An English translation runs into 424 pages. The letters averaged two a week during the year-long period mentioned. It is difficult to see how Zain could have been involved, to any marked degree, in another literary endeavour at the same time.

In his preface to the present work, Zain clearly states that “he assisted at every assembly, where genuine seekers, dependable disciples and loyal servants were present.” Zain’s regularity in attending the assemblies is clear. He also goes on to say that “after putting together this compilation, he approached the exalted Sheikh and personally requested him, in the honourable assembly, to go over whatever this servant, mere dust beneath the feet of the dervishes, had committed to writing.” Thus, “it was read out in the assembly itself, chapter by chapter, word by word, and letter by letter.”

The phrase, “after putting together this compilation” is significant. Clearly, Zain had been recording what had been said and done in the assemblies over a number of years, perhaps four to six years. This was done in the normal chronological manner. It is possible that Zain had this material at hand when the work on The Hundred Letters began. These letters brought home to Zain the benefits of material prepared topic wise, not merely in the necessarily scattered format of a chronological presentation. This could have provided the impetus to put his material into the sixty-three chapters of the present work. Chronology was no longer the organizing factor and was abandoned. It was this ‘compilation’ that Zain brought before his Master, possibly late in 1347, if he had rearranged his material after completing work on The Hundred Letters, with his request that Maneri check what he had written. In chapter 13, devoted to the topic of fasting, after a long discussion on the subject, Maneri commented: “I have written an explanation of this in a letter. For further details it should be consulted.” The letter referred to is “Letter 33: Fasting,” in The Hundred Letters.

This aside needs to be read in the context of the following statement in Zain’s Preface: “Sometimes, during the reading, he would add a suitable anecdote or example to confirm his teaching.” If the material in chapter 13 dates back from a few years previously, and if Zain made his compilation in 1347 and the compilation was read out in the assemblies in 1348, prior to 8th November, Maneri’s comment would make sense. It would mean that the reading reminded Maneri of his letter on fasting, which was still quite fresh in his memory. It should be noted that Maneri had an excellent memory, as his reminiscences, for example, clearly indicate.

Granted that Zain was recording Maneri’s teaching for several years before the whole project of The Hundred Letters was initiated, the question arises as to why he took the trouble of arranging the material topic wise and having it checked by Maneri. The Hundred Letters was a rich mine of spiritual meaning. Zain’s basic motive was his unshakable conviction of the enduring worth of Maneri’s teaching. It had to be recorded for posterity. Added to this was the desire of any author to see his work “in print,” so to say. Zain did not want his efforts to go to waste. There is also the different focus of A Mine of Meaning when compared to The Hundred Letters. While the latter work focussed on the Path to God, the former ranged over a wide spectrum of topics, from minute details regarding the correct way of reciting ritual prayers to deep mystical insights. There was, as it were, “something for everybody” in this work. The two works complemented each other. Moreover, the Letters were addressed to Qazi Shamsuddin, an experienced disciple, while the present work contains answers to a wide variety of questions from participants of varied backgrounds, experience and interest.

A word of explanation seems appropriate about the English rendition of the title. Although the work itself is in Persian, the title is in Arabic. There is nothing unusual about this. Many Persian works have Arabic titles. An author would not hesitate to choose an apt expression for a title to his work if it were in Arabic. A literal translation of the present work would be: The Mine of the Meanings. This is where there is a clash between the constraints of Arabic grammar, specifically in what is called “the construct state,” and the English use of the definite and indefinite articles. A Mine of Meaning is meant to convey in English the sense of the original Arabic title. The singular ‘meaning’ has been preferred to the plural. Undoubtedly the sixty-three-chapter work is replete with ‘meanings.’ The work itself, however, is like a multi-coloured bed cover. Various coloured threads of wool have been carefully woven together to form a pattern. The whole purpose of the cover, however, is to keep a person warm. We might say that the whole purpose of this literary work is to enable the reader to remain ‘warm’ in the knowledge of the multiform relationship that exists between us human beings and God.