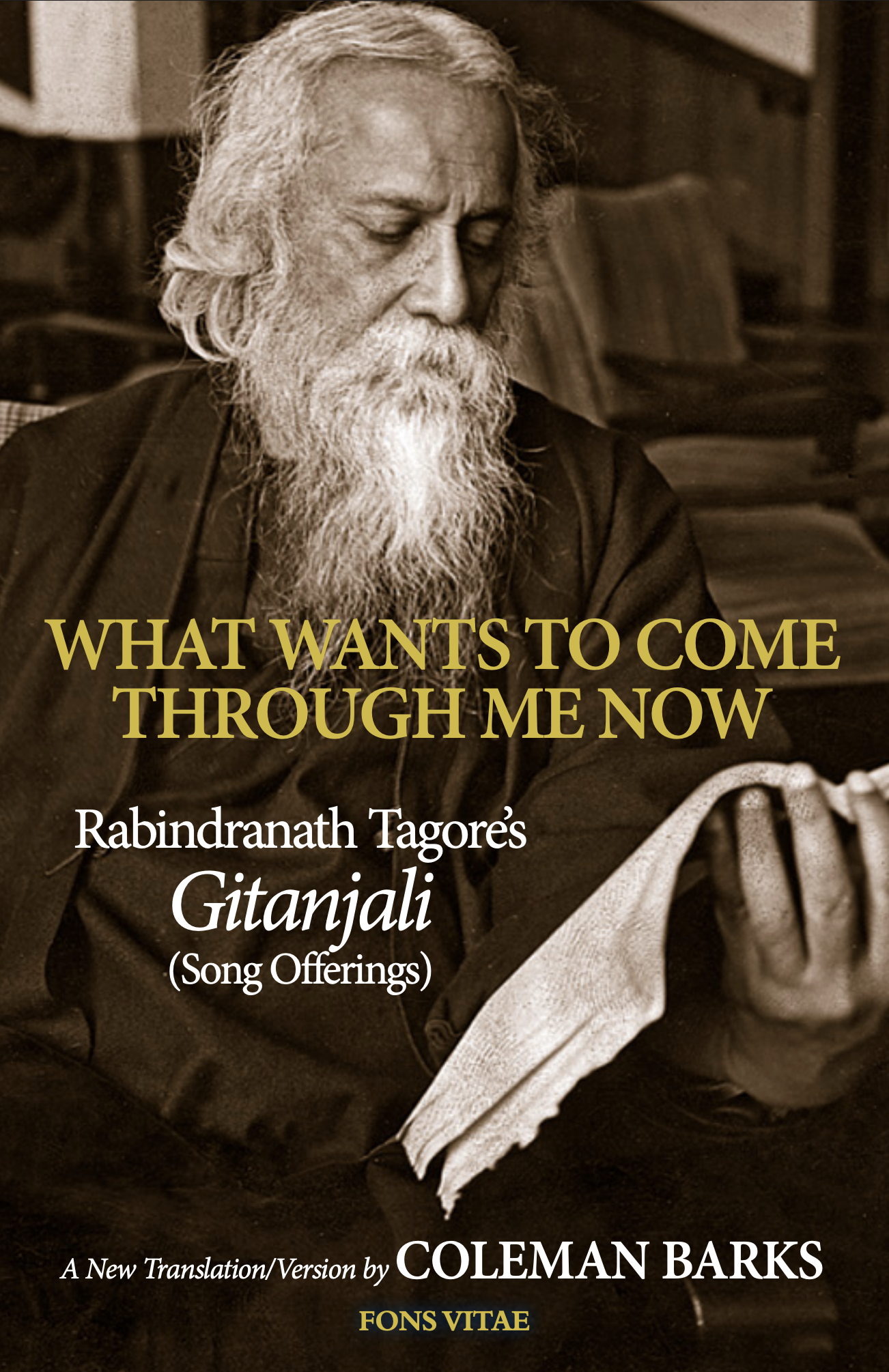

What Wants To Come Through Me Now – Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali (Song Offerings) – Coleman Barks

$24.95

A New Interpretation/Version by COLEMAN BARKS.

FIND OUT MORE about the Fons Vitae ‘SWAGATAM – A Celebration of India & Book Launch (Nov 18, 2021) HERE

Read the ‘Spirituality & Practice’ magazine BOOK REVIEW.

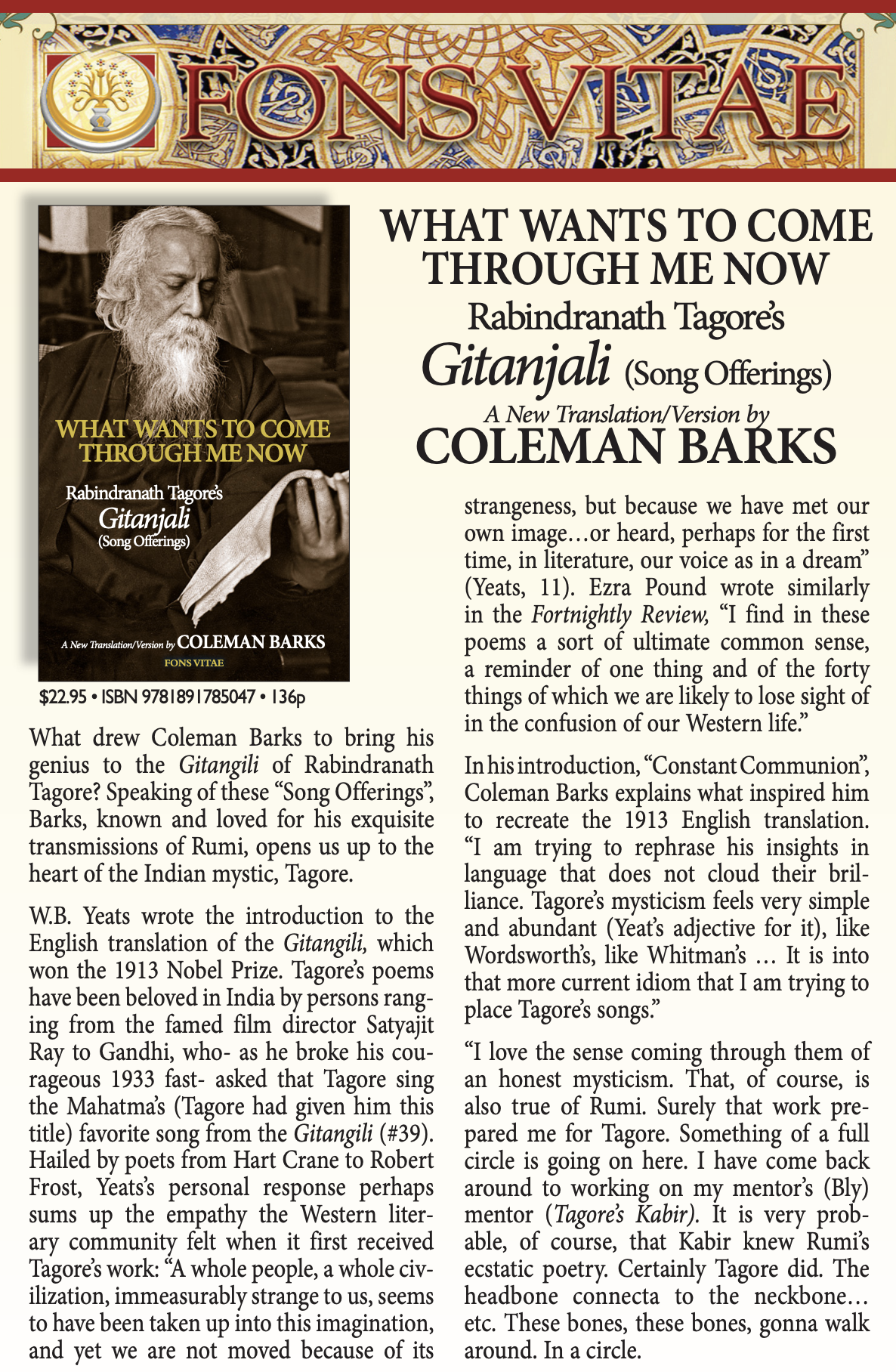

What drew Coleman Barks to bring his genius to the Gitangili of Rabindranath Tagore? Speaking of these “Song Offerings” Barks, known and loved for his exquisite transmissions of Rumi, opens us up to the heart of the Bengali poet and mystic, Rabindranath Tagore. Hailed by poets from Hart Crane to Robert Frost, Yeats’s personal response perhaps sums up the empathy the Western literary community felt when it first received Tagore’s work in 1913: “A whole people, a whole civilization, immeasurably strange to us, seems to have been taken up into this imagination, and yet we are not moved because of its strangeness, but because we have met our own image…or heard, perhaps for the first time, in literature, our voice as in a dream” (Yeats, 11). The 1913 English translation, with an introduction by Yeats, was the winner of the Nobel Prize. Tagore’s poems have been beloved in India by persons ranging from the famed film director Satyajit Ray to Gandhi, who, as he broke his courageous 1933 fast, asked that Tagore sing the Mahatma’s (Tagore had given him this title) favorite song from the Gitanjali, #39. In his introduction, “Constant Communion,” Coleman Barks explains what inspired him to recreate the 1913 English translation. “I am trying to rephrase his insights in language that does not cloud their brilliance. Tagore’s mysticism feels very simple and abundant (Yeat’s adjective for it), like Wordsworth’s, like Whitman’s … It is into that more current idiom that I am trying to place Tagore’s songs.”

“As 2020 moves painfully to realize the Western world’s perception of the diversity of the Earth’s peoples, it is time to celebrate the 1913 recognition bu the Nobel committee of the first Asian collection of poetry/ This is what Coleman Barks has just done in his reinterpretation for English-speaking audiences of Rabindranath Tagore’s Gitanjali. In the elegant poems we have been taught to love in his versions of Rumi, Barks now makes available to all of us Gitanjali of Tagore, a crowning achievement of Hindi Bengali literature. With it he has opened for us the treasures of Hindi spirituality and given new and personal meaning to diversity for the 21st century.” – Elizabeth Kennan Burns, President Emeritus, Mount Holyoke College

Coleman Barks (PhD) is an American poet known for making the poetry of Rumi widely accessible to the English-speaking world through his unique translations, including The Illuminated Rumi (1997), The Essential Rumi (1995), and several other volumes. Barks and his translation work have been featured in an episode of the PBS series “The Language of Life” with Bill Moyers, and in a televised conversation with the late poet, Mary Oliver (listen here: https://lannan.org/events/mary-oliver-with-coleman-barks). He has often produced his Rumi translations in collaboration with music and dance ensembles, including the Paul Winter Consort and Zuleikha. In 2004, Barks received the Juliet Hollister Award for his work supporting interfaith understanding, and in 2006 the University of Tehran awarded Barks an honorary doctorate in recognition of his contributions to the field of Rumi translation. Born and raised in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Barks’s own poetry, influenced by Wordsworth, Whitman, and Rilke, is lyrical, meditative, and steeped in his native Southeastern landscape. He received his PhD from the University of North Carolina, and is a former literature faculty member of the University of Georgia in Athens, where he currently resides.

W.B. Yeats wrote the introduction to the English translation of the Gitangili, which won the 1913 Nobel Prize. Tagore’s poems have been beloved in India by persons ranging from the famed film director Satyajit Ray to Gandhi, who- as he broke his courageous 1933 fast- asked that Tagore sing the Mahatma’s (Tagore had given him this title) favorite song from the Gitangili (#39).

Hailed by poets from Hart Crane to Robert Frost, Yeats’s personal response perhaps sums up the empathy the Western literary community felt when it first received Tagore’s work: “A whole people, a whole civilization, immeasurably strange to us, seems to have been taken up into this imagination, and yet we are not moved because of its strangeness, but because we have met our own image…or heard, perhaps for the first time, in literature, our voice as in a dream” (Yeats, 11). Ezra Pound wrote similarly in the Fortnightly Review, “I find in these poems a sort of ultimate common sense, a reminder of one thing and of the forty things of which we are likely to lose sight of in the confusion of our Western life.”

In his introduction, “Constant Communion”, Coleman Barks explains what inspired him to recreate the 1913 English translation. “I am trying to rephrase his insights in language that does not cloud their brilliance. Tagore’s mysticism feels very simple and abundant (Yeat’s adjective for it), like Wordsworth’s, like Whitman’s … It is into that more current idiom that I am trying to place Tagore’s songs.”

“I love the sense coming through them of an honest mysticism. That, of course, is also true of Rumi. Surely that work prepared me for Tagore. Something of a full circle is going on here. I have come back around to working on my mentor’s (Bly) mentor (Tagore’s Kabir). It is very probable, of course, that Kabir knew Rumi’s ecstatic poetry. Certainly Tagore did. The headbone connected to the neckbone… etc. These bones, these bones, gonna walk around. In a circle.

—

- 9781891785047

- Paperback

- 136